MEMPHIS, Tenn. — A sense of place has long permeated the music of J.D. Wilkes. He’s a native of Paducah, Kentucky, a city located at the confluence of various rivers and cultures — an area where musical variety is in the air and in the blood memory of its people.

“Of course, there’s bluegrass and hillbilly songs, but also blues, jazz, old time fiddle music, jug band music, even swamp rock,” says Wilkes. “It’s a great intersection there. I think I epitomize that in the way that I write and perform.”

Wilkes’ solo debut, Fire Dream, represents the apotheoses of that vision: a hillbilly-gypsy epic, it’s an album of art damaged cabaret music, leavened by Latin rhythms and high lonesome hollers. Call it boho bluegrass — maybe what Tom Waits would sound like if he were a Kentucky Colonel (a title that Wilkes happens to hold).

The album is due out on Big Legal Mess through Fat Possum Records on (February TK), 2018.

Proving a compelling firebrand of American roots music during his two decades leading experimental rockabilly group Legendary Shack Shakers, Wilkes has a resume and passions that extend far and wide. A visual artist, filmmaker and author, he’s served as a session player for Merle Haggard, helped soundtrack HBO’s True Blood, penned a pair of books (The Vine That Ate the South and Barn Dances and Jamborees Across Kentucky) and worked as an ethnomusicologist without portfolio, documenting the dying hillbilly culture of Kentucky.

Wilkes’ creative approach is defined by his home region’s rich history as a musical nexus. “Western Kentucky is unique in that a lot of that mountain music, which is otherwise stuck in Appalachia, trickled down and permeated our conscience,” he says. “But if you look at it topographically we’re a flat delta lowland region, a flood zone … so we have a lot in common with the Mississippi Delta and Memphis and we got all that jazz and blues that came up the river as well.”

That keen understanding of history is partly what drew the interest of Fat Possum’s Big Legal Mess imprint, which signed Wilkes in 2017. “They saw me as a kindred spirit,” he says, “in my efforts to archive and field-record and report upon some form of folk music that’s in danger of being forgotten.”

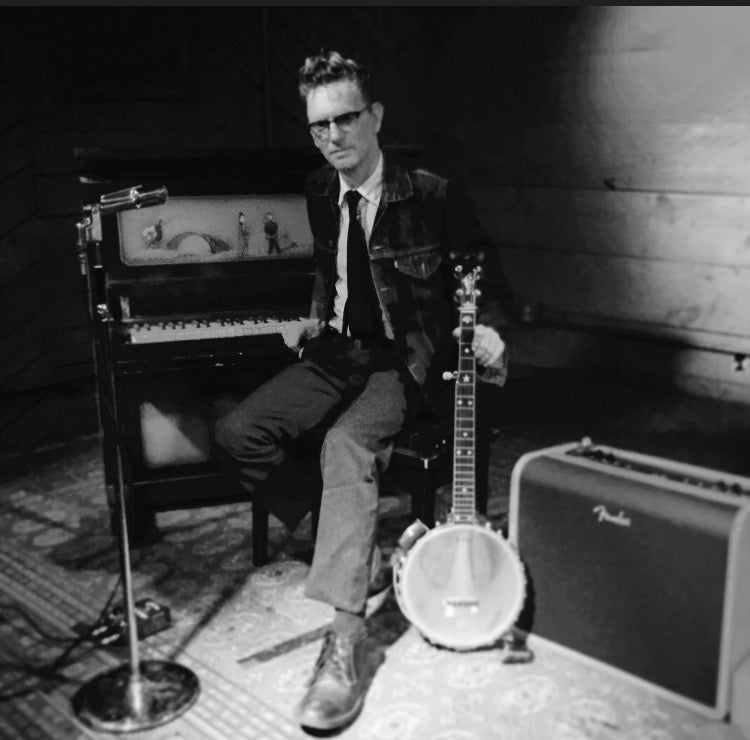

For his solo debut, however, Wilkes has something more outré in mind than a mere musical lesson or genre exercise. Recorded at Delta-Sonic Sound in Memphis with producer Bruce Watson and Jimbo Mathus, the album finds Wilkes creating a complex tapestry of styles and sounds, playing banjo, harmonica, and piano, adding percussion, and even winding up an old hurdy-gurdy. Aiding him in that effort are a couple kindred musical spirits in guitarist Mathus and multi-instrumentalist Dr. Sick from the ever-eclectic Squirrel Nut Zippers.

“They were the perfect people to bring in. They could play any kind of style,” says Wilkes. “Jimbo has such an intuitive feel for blues and Dr. Sick, man, he’s the most amazing musician I’ve ever had the privilege of playing with. I don’t even know what his real name is, but that guy is awesome.” Rounding out the recording are contributions from Drive-By Truckers bassist Matt Patton, up-and-coming soul chanteuse Liz Brasher on backing vocals, and the horn section from Bluff City R&B band, The Bo-Keys.

The album’s opening and title track “Fire Dream” establishes the tone with a cinematic setup. “It sounds as if a gypsy carnival blew in on a tornado and landed in a hillbilly junkyard,” says Wilkes of the tune. “I tried to pay attention to the texture of the songs, both what was in them and how they connected to each other, and the record as a whole.”

Within its ten tracks Fire Dream contains multitudes: from galloping string rambles (“Wild Bill Jones”) to slow burning laments (“Walk Between the Raindrops”), hardscrabble narratives (“Hoboes Are My Heroes”) exotic nocturnes (“Moonbottle”), and hellfire comedy (“Bible, Candle and a Skull”).

The sprite, horn-heavy “Down in the Hidey Hole,” meanwhile, is something Wilkes describes as “apocalyptic ska.” “Basically, it’s about hunkering down in a bomb shelter with your lady to ride out the end of the world,” he says. “It’s happy, upbeat music … but with an ominous edge. That’s what I love about people like Hank Williams; they had great danceable tunes with a dark story at their core.”

Wilkes’ acid wit shines through on Fire Dream, with his lyrics coming across as both highly crafted and deeply intuitive. “A song is like a puzzle, you have to feel around and figure out how the words fit,” he says. “It doesn’t matter if it’s Hank, Bob Dylan, Tom Waits or Nick Cave, they all have a knack for knowing the most artful way the words can collide with one another, or flow together.”

Wilkes notes that there’s underlying emotional edge to record, much of that coming from the fallout of a recent divorce. While he dealt with the end of his marriage more directly on the Shack Shakers last LP — the howling After You’ve Gone — Fire Dream finds light among the shade. “I’m getting back to playing around with things again, musically and lyrically,” he says, “though an element of that darkness still lingers.”

Though hailed for his acrobatic, incendiary live performances with the Shack Shakers, Wilkes says it will be a different kind of roadshow when he begins playing in support of Fire Dream in the spring.

“I plan on approaching the songs more artfully live. I might be sitting on a chair playing banjo instead of jumping in the crowd like I do with the band,” says Wilkes, who plans on touring with an acoustic combo, his 64-key Tom Thumb piano and his usual on stage intensity.

“I’ll still want to entertain, it might just be more with my eyes and voice than my body,” he says. “There’s a lot of stories and a lot of mysteries being revealed in these songs, and that provides its own kind of animation. That’s what I love about this record and this music … it moves.”