Willem Maker

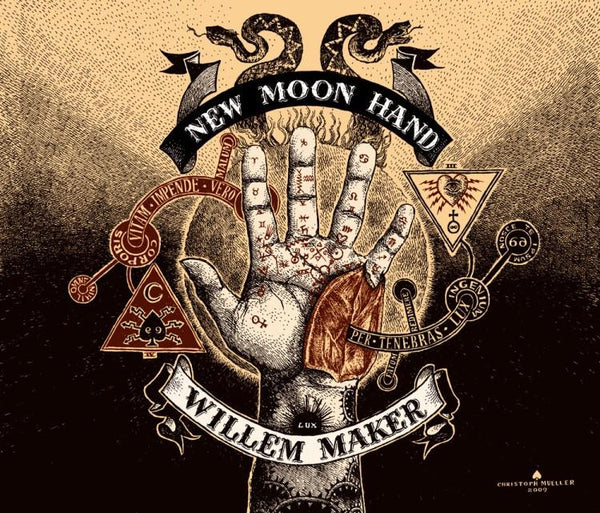

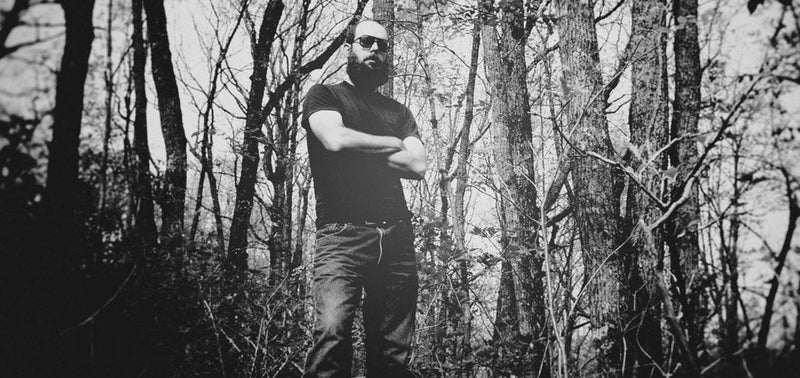

In a soft Southern drawl that stands in stark contrast to the raw howl of his singing, Willem Maker looks out from his home on Turkey Heaven Mountain in East Alabama and says with what sounds like relief, “It´s the middle of nowhere.” The rural beauty of his home tends to find its way into his songs, which weld the molten electric guitars of Neil Young´s Crazy Horse with the melodicism of Nick Drake and the lyricism of Townes Van Zandt. But for Maker, it has been a perilous and painstaking path to Turkey Heaven Mountain-a gut wrenching mental, emotional and spiritual journey that he unflinchingly chronicles on his new album New Moon Hand, due out on Big Legal Mess Records in March.

A follow-up to Stars Fell On, the acclaimed debut that he recorded alone at home, New Moon Hand finds Maker joined by such blues and rock and roll luminaries as Alvin Youngblood Hart, Jim Dickinson and Cedric Burnside. But despite the distinctiveness of the contributors, the sound is uniquely his own, and Maker establishes himself as a brilliant emerging artist with a story few can imagine.

The son of a drag racer, Maker grew up on the rural Southern stock car racing circuit, spending an isolated childhood in West Georgia and Tennessee. Encouraged by his older brother, Maker showed an early talent for music and took up the bass, learning by playing along to classic rock radio and his Metallica records. When his father took a job for industrial giant Southwire, a wire manufacturer, the family eventually settled in Carrollton, Georgia, where Maker spent his teenage years.

While living in Carrollton, Maker committed himself to music more seriously and began writing his own songs. He formed the band Ithica Gin with his brother Sloane and quickly developed a local following. An early single was produced by Jay Farrar and the band received an offer to play with Ryan Adams. But Maker´s promising start was cut short by a tragic turn of fate.

While still in his teens, Maker began to experience severe, unexplainable manic episodes. The mania most closely resembled the onset of bipolar disorder with one disturbing difference. Those suffering from bipolar disorder have no memory of their manic episodes, but Maker was hyperconscious-wracked by an intense, dizzying mania that could last for days. Medical specialists were baffled and struggled for a diagnosis. It was not until much later that Maker and his family learned the cause: severe lead and mercury poisoning.

“It´s a real dirty tale of what went down in that town,” Maker says. “Supposedly, Carroll County is one of the top three dioxin hot spots in the world. They would illegally dispose copper slag and the residue from the smelter, dump it into farmer´s fields and use it as back fills. The slag is highly toxic, and it was all around the house we rented. They used it as back fill around the basement, where we rehearsed and where I spent all my time. The air was pure poison.”

Just nineteen, and wracked by the mysterious, disturbing episodes, Maker was hospitalized at Ridgeview Institute, a psychiatric center in Smyrna, Georgia. In a strange twist of fate, Maker´s roommate at Ridgeview was Joe South, the legendary singer-songwriter who wrote Grammy-winning classics like “Games People Play” and “Walk a Mile in My Shoes” before depression and mental illness derailed his own musical career.

“They took me to my room, and there he was. I don´t think I had slept for like two weeks going in there and they put me on Haldol, which I think at the time was the strongest stuff there was. I remember walking into the room and Joe was laying on the bed with his arms behind his head. His presence was really comforting, and I talked to him about music and how I was really optimistic about the future and the band. It was really weird that I was talking to him about that stuff, and me and my brother, because Joe played with his brother and his brother died tragically. He was real quiet. I just remember him being really caring, and really patient. And then I was out in the lobby one day, and there were some people to see him, and then he was gone.”

Maker resisted all attempts to put him on medication, determined to find other answers to what was happening to him. “They wanted to put me on lithium and all that, but I knew something else was at work. I found this holistic doctor and over time, we learned about heavy metal poisoning. He turned me on to this therapist in Atlanta, who was really the lifesaver. If I hadn´t met her, I don´t think I would be alive. I was just lost at sea. All this stuff had flown through my door and I didn´t know how to make sense of it. I couldn´t figure out how to integrate into everyday life.”

Drawing from the electric, hallucinatory creativity of his manic episodes, Maker began writing feverishly, filling notebook after notebook with lyrics. It was a long and slow recovery. Eventually, alone and settled on Turkey Heaven Mountain, Maker began recording his music.

“My grandfather was a bootlegger till the day he died, and I´ve always thought of my home studio as like a moonshine still,” Maker laughs. “I´m trying to make the best brew possible.”

For Maker, the process of writing and recording became a deeply creative exploration of his life and what had been revealed to him during the episodes. “I felt like I had woken up, and there was a lot of stuff that needed to come out of me,” he says. The result was Stars Fell On, recorded alone on Turkey Heaven Mountain, and the songs that formed the basis for New Moon Hand, Maker´s new album on Big Legal Mess.

Recorded on Turkey Heaven Mountain but also in Nashville and Memphis, New Moon Hand continues the rich lyricism and punishing blues-based guitar of Stars Fell On. It also features appearances by close friends of the Fat Possum/Big Legal Mess family-notably Scott Bomar, who played and handled production with Maker, Memphis legend Jim Dickinson on piano and organ, Cedric Burnside on drums, and the powerhouse Alvin Youngblood Hart on guitar. The result is an album of tremendous power and delicacy-from the grinding open-tuned slide guitar of “Black Beach Boogie” to the soulful, Sticky Fingers-era Stones-y “White Ladye” to the sparse piano of the lovely “Saints Weep Wine.” In the latter, in a plaintive rasp, Maker sings, “Leave the fever in the past / Ready the plow and sharpen the axe / Raise the dead, love / Rise to the task / Outlast / Outlast.”

“Saints Weep Wine” offers a hopeful, shimmering reflection of Maker´s recovery, which is countered later by the chilling “Lead & Mercury”: “There´s poison lead and mercury / rainin´ down on our heads / on our babies´ beds / Stole my youth / Took my brightest days.” The two songs offer perspectives not only on what Maker went through, but also on the depth and span of his talent as a writer and musician. It is incredible that Maker could emerge from such pain with so much powerful music-but even more amazing is Maker´s ability to find hope, beauty and even inspiration in it.

“What I had is actually called a spiritual emergency,” Maker says. “That´s the actual term for it. It´s not a chronic mental illness; it´s a moment when someone is going through an intense change. It is a moment of fast evolution. It was like I had a prolonged near-death experience due to the toxic poisoning. That´s the core of my work, learning to understand that and integrate all the stuff that had come in. It was an unstable experience, but it was also like the richest experience of my life, which is something people can´t get their heads around. But you know, we´re all vulnerable in that way. It´s surprising just how fragile everything can be.”